The KGB's Holy War: How Soviet Intelligence Created Liberation Theology

In 1978, the highest-ranking intelligence officer ever to defect from the Soviet bloc arrived in the United States with secrets that would reshape our understanding of the Cold War. Ion Mihai Pacepa, a general in Communist Romania's secret police, carried with him detailed knowledge of one of the KGB's most audacious operations: the creation of an entire religious movement designed to destabilize the Western Hemisphere.

The operation had a name, Liberation Theology. And according to Pacepa, it was born not in the slums of Latin America or in the hearts of priests ministering to the poor, but in the Lubyanka, headquarters of the KGB.

Pacepa learned the details from Soviet General Aleksandr Sakharovsky, who served as communist Romania's chief foreign intelligence adviser and Pacepa's de facto boss until 1956. That year, Sakharovsky ascended to head the PGU—the First Chief Directorate of the KGB—a position he would hold for an unprecedented 15 years. During the Cold War's hottest years, Sakharovsky's identity was so closely guarded that not even all members of the Israeli and British governments knew who ran the Mossad or MI-6. But his fingerprints were all over history's pivotal moments.

Sakharovsky authored the export of communism to Cuba between 1958 and 1961. His handling of the Berlin crisis during those same years generated the Berlin Wall. His Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. And in October 1959, he orchestrated what would become the opening move in the Soviet campaign to control Latin America through religion.

On October 26 of that year, Sakharovsky and his boss, Nikita Khrushchev, arrived in Romania for what was billed as "Khrushchev's six-day vacation." It was no vacation. Khrushchev wanted to go down in history as the Soviet leader who exported communism to Central and South America. Romania was the only Latin country in the Soviet bloc, and Khrushchev wanted to enroll her "Latin leaders" in his new "liberation" war.

The KGB had a penchant for "liberation" movements during those years. The National Liberation Army of Colombia—FARC—was created by the KGB with help from Fidel Castro. The National Liberation Army of Bolivia was created by the KGB with help from Che Guevara. The Palestine Liberation Organization was created by the KGB with help from Yasser Arafat. All were born at the Lubyanka. Liberation Theology would be next.

The Dezinformatsiya Program

The birth of Liberation Theology came through a 1960 super-secret "Party-State Dezinformatsiya Program" approved by Aleksandr Shelepin, chairman of the KGB, and Politburo member Aleksey Kirichenko, who coordinated the Communist Party's international policies. The program's demand was simple and audacious: The KGB would take secret control of the World Council of Churches, based in Geneva, Switzerland, and use it as cover for converting Liberation Theology into a South American revolutionary tool.

The target was ideal. The WCC was the largest international ecumenical organization after the Vatican, representing some 550 million Christians of various denominations throughout 120 countries. Control it, and you could influence the spiritual and political orientation of hundreds of millions.

But you can't simply hijack an organization that large overnight. The KGB began by building an intermediate structure—an international religious organization called the Christian Peace Conference, headquartered in Prague. Its main task was to bring the KGB-created Liberation Theology into the real world. The Christian Peace Conference was managed by the KGB and subordinated to the World Peace Council, another KGB creation founded in 1949 and also headquartered in Prague by then.

Pacepa knew the World Peace Council intimately. During his years at the top of the Soviet bloc intelligence community, he managed the Romanian operations of the WPC. "It was as purely KGB as it gets," he would later say. Most of the WPC's employees were undercover Soviet bloc intelligence officers. The WPC's two publications in French—Nouvelles perspectives and Courier de la Paix—were managed by undercover KGB and Romanian DIE intelligence officers. Even the money came from Moscow, delivered by the KGB in laundered cash dollars to hide their Soviet origin.

In 1989, when the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, the World Peace Council publicly admitted that 90 percent of its money came from the KGB.

Medellin 1968

In 1968, the pieces came together. The KGB-created Christian Peace Conference, supported by the worldwide World Peace Council, maneuvered a group of leftist South American bishops into holding a Conference of Latin American Bishops at Medellín, Colombia. The conference's official task was to ameliorate poverty—a noble goal no one could oppose. Its undeclared goal was to recognize a new religious movement encouraging the poor to rebel against the "institutionalized violence of poverty," and to recommend this new movement to the World Council of Churches for official approval.

The Medellín Conference achieved both goals. It also adopted the KGB-born name: Liberation Theology.

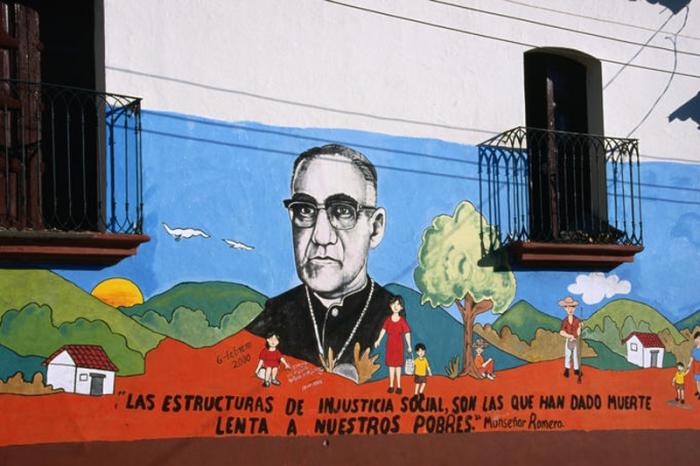

The operation was complete. What had begun in Moscow in 1960 as a dezinformatsiya program had, by 1968, manifested as a religious movement with official sanction from hundreds of Latin American bishops. The movement would go on to reshape Catholic politics across the hemisphere, aligning priests and bishops with revolutionary movements from Nicaragua to El Salvador, from Chile to Brazil.

The Unanswered Questions

Liberation Theology had key leaders, famous pastoral figures and intellectuals who gave it legitimacy and theological heft. There were bishops like Sergio Méndez Arceo from Mexico and Helder Câmara from Brazil. There were theologians like Leonardo Boff, Frei Betto, Henry Camacho, and most notably, Gustavo Gutiérrez, whose 1971 book A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, Salvation became the movement's foundational text.

Pacepa said he had "good reason to suspect that there was an organic connection between the KGB and some of those leading promoters of Liberation Theology," but he had no evidence to prove it. For the last 15 years of his life in Romania—1963 to 1978—he managed that country's scientific and technological espionage, as well as the disinformation operations aimed at improving Ceausescu's stature in the West. He wasn't involved in the creation of Liberation Theology per se.

Still, when he glanced through Gutiérrez's book, he had a feeling. "I had the feeling that it was written at the Lubyanka," Pacepa said. "No wonder he is now credited with being the founder of Liberation Theology."

From feelings to facts, however, is a long way. And that's where the story gets interesting—and troubling. Because what Pacepa's testimony reveals is not just that the KGB created a religious movement, but that the movement's true origins remain obscured. The priests and bishops who embraced Liberation Theology may well have done so with pure intentions, genuinely moved by the plight of the poor. The theologians who gave it intellectual structure may have believed they were recovering Christianity's radical roots.

But the framework within which they operated, the organizations that supported them, the conferences that legitimized them, and even the name of their movement—all of it, according to one of the highest-ranking intelligence defectors in history, came from Moscow.

The question that remains unanswered is this: How many of Liberation Theology's leaders knew? How many were willing participants in the Soviet operation, and how many were useful idiots, manipulated by handlers they never met, serving a cause they didn't understand?

Pacepa couldn't say. And nearly half a century after Medellín, with most of the principals dead and the Soviet archives still largely closed, we may never know. What we do know is that one of the 20th century's most influential religious movements—a movement that shaped the politics of an entire hemisphere and continues to influence Catholic social teaching today—was born in the same building where the Soviet Union planned its wars of conquest.

That's not a conspiracy theory. That's the testimony of a general who was there.